DCW: Most Read in 2025

Since going fully online in May 2024, DCW has seen significant growth. The addition of eBooks, CPDs, an expanded archive,

The “Dark Fleet” exposes financial institutions to sanctions violations, lawsuits, and losses. Learn how to mitigate these hidden risks.

This report was initially published by Blackstone Compliance, Pole Star Global, and the Deep Blue Intelligence team in June 2024. It has been updated by the authors and republished to address additional concerns arising from Dark Fleet tactics facing financial institutions and to incorporate recent guidance by OFAC, other U.S. government agencies, and those of members of the Price Cap Coalition.

In March 2024, the Dali, a Singapore-flagged vessel, crashed into Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key bridge. Six lives were lost and the mishap will likely cost billions of US dollars in reconstruction, salvage, and insurance claims. However, the Dali was insured by a good protection and indemnity club (“P&I Club”), and chartered, crewed, classed, and flagged by reputable companies. As horrendous as the crash was, Baltimore will have the money to rebuild and all parties can be held to their obligations.

Meanwhile, across the world, a group of about 850 tankers acquired to evade Russian, Iranian, and Venezuelan sanctions, serves as a ticking time bomb for an equally disastrous crisis, but which will most likely not be covered by insurance and where the threat actors involved are not held accountable. First acknowledged by OFAC and its coalition partners (the “Coalition”)[[1]] in October 2023,[[2]] the Coalition notes that “[t]his shadow trade is characterized by irregular and often high-risk shipping practices that generate significant concerns for both the public and private sectors.[[3]],[[4]]”

Dealing with the Dark Fleet not only places companies in peril of violating sanctions laws, but also being left on the hook to foot the bill for a disaster. The Coalition notes that the Dark Fleet often “neglect[s] the appropriate surveys or inspections” and “rel[ies] on unproven … insurance providers.[[5]]” In typical litigious fashion, this is an understatement. While many Dark Fleet vessels use deceit to obtain maritime services – classification, insurance, and flagging – from providers in Coalition countries, many Dark Fleet vessels also obtain those services from high-risk enablers who appear to cater to vessels engaged in sanctions evasion. Their deceitful practices – engaging in high risk and undeclared ship-to-ship transfers and providing fake navigational information close to shore – increase the risk of a collision.

All vessels, including those in the Dark Fleet, require access to maritime services to operate. These include flagging, insurance, classification, and corporate formation services. Vessels without a flag or insurance can’t visit a port and vessels without safety certificates from classification societies can’t obtain insurance. Flag states require both classification certificates and insurance.

Dark Fleet members actively seek out maritime services provided by Coalition partners. Access to the International Group of P&I Clubs (the “IG”) offers the legitimacy needed to open doors that would otherwise be closed, such as re-assuring charterers that their tanker is safe and fully insured. Safety certificates issued by classification societies within the International Association of Classification Societies (“IACS”) are viewed as the gold standard, even by OFAC.[[6]]

There are plenty of other maritime service providers operating outside of the IG and IACS. Many of them may be able to ensure a vessel adheres to high standards or are able to cover a mishap because they have relationships with re-insurers. Many of these companies may be high risk for other reasons, such as Ingosstrakh, Russia’s state-owned P&I club. But what happens when a vessel is too “toxic”, even for Ingosstrakh or a similar high-risk P&I club?

The answers are maritime service providers of last resort. There are a series of flags, insurers, and classification societies that appear to cater to vessels which are evading sanctions or are engaged in high-risk activity. Threat actors know that they aren’t obtaining real insurance when they are engaging in a P&I Club of Last Resort (“PILR”) or obtaining safety certificates from tiny no-name companies. Instead, they are looking for the veneer of legitimacy to convince a port operator to let them dock, or to be flagged by a large reputable company.

While the Dark Fleet has obtained access to Coalition maritime services, that has mostly been through deceit and clandestine activity. Coalition providers maintain compliance programs and are actively trying to enforce sanctions. Yes, our industry can improve its controls, but the vast majority of slip-ups are neither willful nor reckless. Conversely, high-risk enablers (“enablers”) are maritime service providers which actively solicit business from sanctioned vessels or those engaged in malign conduct.

At the time of this review, over a quarter (28%) of the Dark Fleet uses a P&I club, classification society, or flag registry which is categorized as a high-risk enabler. These enablers can vary by jurisdiction and how they conduct business. They frequently attempt to operate under the radar, assuming low key and generic names to confuse the maritime industry. For example, some of the identified PILR operating in this manner include:

Some enablers are more open about their business. For example, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, several flags have taken advantage of the situation by opening their registries to vessels that aren’t welcome elsewhere. One flag, which is managed by a private company located in the United Arab Emirates,[[13]] makes no qualms about the vessels it registers. Almost all of their tankers are engaged in some form of suspicious or questionable activity, including:

Concerningly, the flag took on Sovcomflot’s vessels, Russia’s state-owned tanker company, after they were designated by OFAC and forced to de-list from their former flag. Sovcomflot’s designation was announced by the U.S. Treasury with great fanfare,[[16]] and the flag would almost certainly have understood the risks of providing material assistance to these vessels.

A major Dark Fleet casualty or oil spill would be an economic and ecological catastrophe. Without proper insurance and accountability, local governments – often the victim – would be forced to cover the expenses and damage. Whether it is from picking up Venezuelan crude in the Caribbean or discharging Iranian crude at a Chinese port, the local economies would be forced to finance the cleanup and any parties to the transactions, from commodities traders to banks, would almost certainly be subject to billions of dollars in lawsuits.

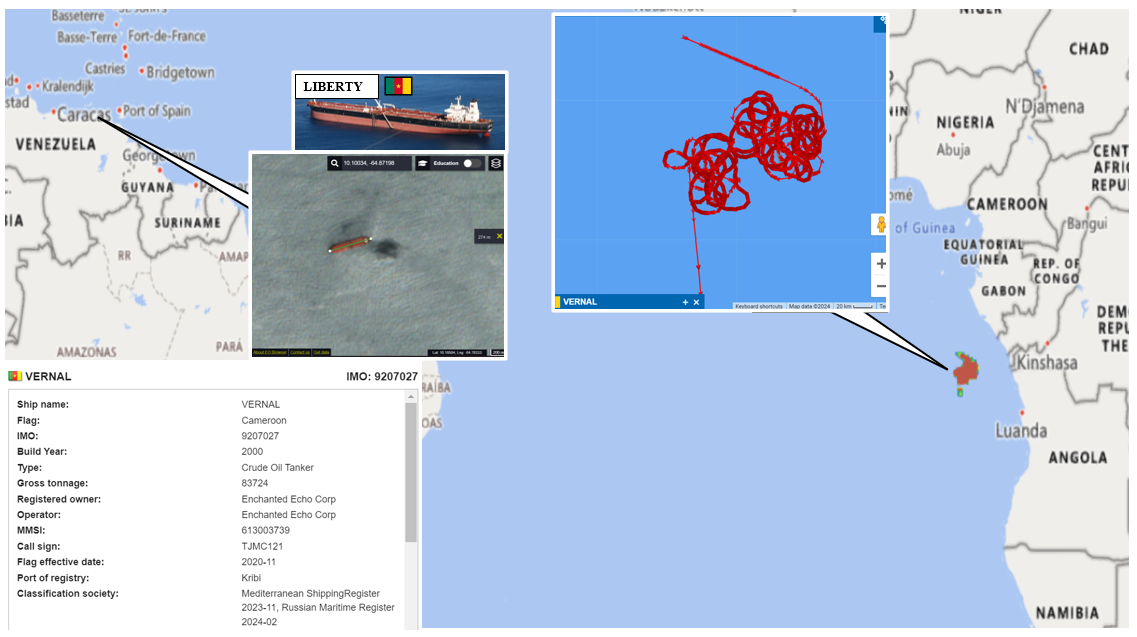

The example of the Liberty[[17]] (IMO 9207027) is instructive. The Liberty ran aground off of Indonesia on 2 December 2023.[[18]] She was laden with crude from Venezuela’s Jose Terminal, which she loaded between 29 August – 3 October 2023. During that period, the Liberty had been spoofing her signal as off of Angola.

Any parties to the transactions, from commodities traders to banks, would almost certainly be subject to billions of dollars in lawsuits.

The Liberty was insured by Continental P&I Club (“Continental”), a PILR. Deep Blue Intelligence has exhaustively identified all of the tankers Continental underwrites. Two of their vessels were subject to sanctions directly,[[19]] over half are engaged in advanced deceptive shipping practices (“ADSP”) such as spoofing, and the remaining deal in Russian crude. While they purport to be an Estonian insurance firm,[[20]] their name servers tie back to Russia[[21]] and they were incorporated in the Marshall Islands.

After the Liberty ran aground, it quickly became apparent that Continental couldn’t cover the mishap. Fortunately, the Liberty did not rupture and cause a major oil spill, otherwise it’s not apparent who would be able to foot the cleanup’s bill, as all parties to the transaction would not be able to afford it, and/or are positioned outside the long arm of the law.

Unfortunately, this is not a one-off, even for Continental. The Pablo,[[25]] also underwritten by Continental and allegedly returning from delivering Iranian crude[[26]], exploded in the Malacca Straits. She was flagged by an enabler and never listed her classification society.

Not content with simply using questionable insurers and certifiers, many Dark Fleet vessels double down on risks by engaging in unsafe behavior on the high seas. For many high-risk enablers, these practices are a feature, not a bug. These include the frequent use of faking their vessel’s location (i.e., spoofing), not broadcasting their position in crowded waterways, or engaging in ship-to-ship transfers in unsafe locations such as open seas.

A quarter of all vessels which are flagged, classed, or insured by a high-risk enabler have spoofed their locations. Another quarter, mostly mutually exclusive of those spoofing, routinely disable their AIS or conduct ship-to-ship transfers involving Iranian or potentially sanctioned cargo. Anytime a vessel is providing false or no positional information to nearby vessels, it increases the likelihood of a collision or mishap.

Some threat actors are more aggressive with their spoofing practices than others. One such operator is Safe Seas Ship Management FZE (“Safe Seas”), an Emirati company placed under U.S. sanctions for their support of Iran’s armed forces. [[27]] OFAC placed sanctions on Safe Seas and five of their vessels, predominantly on the basis that one vessel, the CHEM (IMO 9240914) was identified in leaked emails for shipping crude on behalf of Sahara Thunder, an Iranian front company. OFAC also designated an additional five vessels but did not designate 31 other vessels managed by Safe Seas.

Ironically, Safe Seas’ spoofing practices are extremely unsafe. While most spoofers fake their locations just outside of busy anchorages – close enough to look plausible but away from other ships who might report the false contact, Safe Seas vessels have faked their positions within Iraqi harbors such as Khor Al Zubair – high traffic areas which vessels need to carefully navigate. Unlike most Persian Gulf ports, Iraq’s oil and LPG terminals sit between 50-70km inland within a narrow channel.

Therefore, it’s shocking when one of Safe Seas’ vessels, the Zenith Faith (IMO 9387152), pretends to be in the center of a channel that’s less than 400 meters long in low tide. Tanker vessels can be between 30-50 meters in breadth and neither turn quickly nor stop on short notice. While the crew may be able to visually confirm there is no vessel there under good weather conditions, this behavior has the potential to cause a major accident during periods of low visibility, or to even simply panic a vessel crew on an ordinary day.

The maritime community has escaped a Dark Fleet disaster at least three times, but being lucky is not a strategy. Regardless of a jurisdiction’s view on Coalition sanctions, it’s in all parties’ best interest to clamp down on high-risk enablers. Chinese port operators would be just as woeful in covering billions of damages as a U.S.-based flag registry. Unwitting financiers and traders would be flabbergasted to receive a civil – and potentially criminal – subpoena for their interactions with such a vessel.

Unfortunately, insurance and safety documentation from high-risk enablers is – likely unwittingly – accepted by large and reputable maritime organizations. Flag states frequently publish which P&I clubs they accept insurance from and high-risk enablers are included within these lists. Coalition P&I clubs currently cover 17% of the Dark Fleet vessels which are supported by high-risk classification societies and/or flags. Forty percent of Dark Fleet vessels insured or classed by a high-risk enabler are flagged by either registries in the G-7, E.U., or a Big-3 flag. [[28]]

It’s not hyperbole to say high-risk enablers pose an existential risk to all parties who deal with them, all while the real culprits would abscond to Russia, Iran, or any other friendly territory. Without adequate maritime intelligence, trade finance departments remain at risk not just for sanctions violations, but also future lawsuits or being stuck financing a transaction where the buyer or seller cannot sell cargo because it is sanctioned. At the same time, financial institutions do not always have the same level of information to vet vessels in a transaction as the commodity trader they are financing.

To mitigate these risks, we recommend:

The maritime sanctions landscape has become increasingly complex. The consequences for non-compliance are severe and exceed the risks of a penalty from OFAC. They range from becoming entangled in billion-dollar lawsuits to having cargo, and the financial liquidity backing it, becoming frozen by OFAC while the goods are on the water. However, with careful due diligence and support from a community of professionals, financial institutions can mitigate these risks and pave the way for new, safer business for years to come.

Disclosure Note: Blackstone Compliance, Pole Star Global, and Deep Blue Intelligence sell vessel tracking and maritime intelligence services.

About the authors: David Tannenbaum is the director of Blackstone Compliance Services, a sanctions and AML advisory firm. David previously served at OFAC and has almost 15 years of experience working with Top-10 and Top-50 global financial institutions to develop, implement, and enhance their global sanctions and AML programs.

Pole Star Global is the premier provider of maritime intelligence to financial institutions. Its products, including PurpleTrac, are used to screen and track vessels for sanctions risks. Pole Star also serves clients in the maritime industry including the world’s three largest flag states, the U.S. Department of Defense, and other governments in keeping their waters safe and secure.

Deep Blue Intelligence is a joint threat intelligence program between Blackstone Compliance and Pole Star Global. It is responsible for identifying maritime sanctions threats ahead of time and assisting its customers in addressing those threats.

[[1]]: The Price Cap Coalition consists of the U.S., G7 countries, and Australia. Because the cap applies to EU persons, non-G7 EU countries are often included.

[[2]]: Office of Foreign Assets Control, et. al. Advisory for the Maritime Oil Industry and Related Sectors. 12 October, 2023.

[[3]]: [Office of Foreign Assets Control, et. al. Advisory for the Maritime Oil Industry and Related Sectors. 12 October, 2023, at p.] 1.

[[4]]: OFAC would go on to name the Dark Fleet the “shadow fleet.” The labels are synonymous. Because we’ve been calling it the former well over a year before OFAC acknowledged it, and shall continue to do so. Because we are cool like that.

[[5]]: Ibid.

[[6]]: Ibid

[[7]]: Described at length in the next section.

[[8]]: Adjin, Adis. Malaysia provides details on this month’s big tanker collision. Splash 24/7. 31 July, 2024. Accessed at https://splash247.com/malaysia-provides-details-on-this-months-big-tanker-collision/

[[9]]: East of England P&I Club. About Us. 2024. Accessed at http://eastpandi.com/about-us/.

[[10]]: Wiese Bockman, Michelle. Iran-linked shipowners list little-known ‘East of England’ P&I Club for tanker cover. Lloyds List. 11 February, 2021. Accessed https://lloydslist.com/LL1135759/Iranlinked-shipowners-list-littleknown-East-of-England-PI-Club-for-tanker-cover.

[[11]]: Bockman Wiese, Michelle. UK-incorporated marine insurer claiming government backing issued Blue Cards for sanctioned Iranian trading tankers. Lloyds List Intelligence. 15 October, 2024. Accessed at https://www.lloydslist.com/LL1150979/UK-incorporated-marine-insurer-claiming-government-backing-issued-Blue-Cards-for-sanctioned-Iranian-trading-tankers.

[[12]]: Assurance Foreningen Ltd. Contact us. Accessed at https://www.assuranceltd.net/contact.php. WhoIs available upon request.

[[13]]: Intershipping Services. About Us. Accessed at http://www.intershippingservices.com/about-intershippingservices.php.

[[14]]: See e.g., Verma, Nidhi and Jonathan Saul. Top shipper of Russian oil secures Indian cover as Western certifiers exit. Reuters. 31 May, 2023. Accessed at https://www.reuters.com/business/top-shipper-russian-oil-secures-indian-cover-western-certifiers-exit-2023-05-30/.

[[15]]: See e.g., Office of Foreign Assets Control. Treasury Targets International Network Supporting Iran’s Petrochemical and Petroleum Industries. 23 January, 2020.

[[16]]: Office of Foreign Assets Control. U.S. Treasury Designates Russian State-Owned Sovcomflot, Russia’s Largest Shipping Company. 23 February, 2024.

[[17]]: The Liberty, at the time of writing, is now named the Vernal. She was named the Liberty when she ran aground.

[[18]]: The Maritime Executive. Marshall Islands Shuts Down Insurer With "Dark Fleet" Ties. 14 December, 2023. Accessed at https://maritime-executive.com/article/marshall-islands-shuts-down-insurer-with-dark-fleet-ties.

[[19]]: The Lemur (IMO 9153525) was owned by Bravery Maritime Corp, was designated by OFAC as an oil broker for Iran's Qods Force, a component of the IRGC, on 13 August 2021. It has since been passed rapidly through three shell companies and has undergone five flag changes. The Alisa (IMO 9147447) was designated for dealing in Venezuelan crude in January 2021.

[[20]]: Continental P&I. Contacts. 2020. Accessed at https://continentalpandi.com/contacts/. Accessed on 1 May, 2024.

[[21]]: Domain Tools. WhoIs Record for ContinentalPandI.com. Accessed on 1 May, 2024. Accessed at https://whois.domaintools.com/continentalpandi.com.

[[22]]:Marshall Islands Shuts Down Insurer With "Dark Fleet" Ties.

[[23]]: Paris MOU. Recognized Organization Performance Table 2020 – 2022. 30 June, 2024.

[[24]]: In the U.S., countries cannot claim sovereign immunity if the underlying conduct involves a commercial transaction, such as selling privileges afforded by a country through a third-party. See 28 USC §1605(a)(2).

[[25]]: IMO 9133587

[[26]]: Yerushalmy, J. and Haylena Krishnamoorthy. How a burnt out, abandoned ship reveals the secrets of a shadow tanker network. The Guardian. 17 September, 2023. Accessed at https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/sep/18/how-a-burnt-out-abandoned-ship-reveals-the-secrets-of-a-shadow-tanker-network.

[[27]]: Office of Foreign Assets Control. Treasury Targets Networks Facilitating Illicit Trade and UAV Transfers on Behalf of Iranian Military. 25 April, 2024.

[[28]]: The majority of global tonnage is under three flags, those of Liberia, Marshall Islands, and Panama. All of these flags maintain high standards and are reputable.

[[29]]: Disclosure: Pole Star Global, a co-author of this article, provides vessel tracking software. Blackstone Compliance, a co-author of this article, provides sanctions and anti-money laundering consulting and advice.

[[30]]: Office of Foreign Assets Control, et al. Guidance to Address Illicit Shipping and Sanctions Evasion Practices. 14 May, 2020.

[[31]]: Deep Blue Intelligence, a joint program between Pole Star Global and Blackstone Compliance, and the co-author of this article, provides maritime intelligence watchlists and advice.

[[32]]: Iranian oil traders frequently mislabel their crude as Iraqi or Omani-origin goods. This is likely related to their spoofing patterns, which are typically outside of the anchorages at Basra (Iraq) or Sohar (Oman).

Gain full access to analysis, cases, eBooks and more with a DCW Free Trial